Klinta Trädgård

Two weeks with Peter Korn and Julia Andersson

April 2022 - Tom Nicholls

1. Introduction

I first became aware of Peter Korn when I started volunteering at York Gate Garden in Adel, Leeds. There had been some considerable building work at the garden over the previous couple of years to create new areas of the garden, one of these new areas was a tiered, circular planting area that was to be planted with Mediterranean species, the substrate being pure river sand to a minimum depth of 30cm. Ben Preston and Jack Ogg (head and senior gardeners) explained they had attended the Beth Chatto symposium where they had seen Peters presentation on his methodology and were directly inspired to create a garden using sand as the substrate. They believed it would enable them to push and test the hardiness of various plants that people would expect not to be able to grow in the North of England.

As my studies progressed, I became aware of other people whose methodologies seemed to reference or be linked to Peters, such as James Hitchmough,

Nigel Dunnett, and Cassian Schmidt to name a few. Their work encompasses various ideas of promoting biodiversity, low maintenance yet high ornamental value gardens and public spaces, species selection for future climates and naturalistic design with a deep understanding of the ecology of the species used. I decided to read the Peter Korn book ‘Giving plants what they want’ as a way of trying to understand the thought process behind the new garden and his methodology with the hope that it would be useful for me whilst working at York Gate. I subsequently realised the importance of the work that Peter has done to refine this methodology, its importance as we move to peat free growing mediums, species rich biodiverse spaces and the potential application for civic plantings and gardens in this country. I decided that I would try to contact him to visit and spend some time learning from him.

2. Aims and objectives

I am interested in seeing Peter’s methodology of planting into different substrate mixes including pure sand and the subsequent variation of growth habit, how he creates and maintains his planting designs both public and private and the manipulation of his local environment in the creation of microclimates where he can grow a very wide variety of flora including high alpine species.

Due to the creation of microclimates, Peter Korn is able to grow a large variety of plant species from all over the world. The conversations I have with Peter, observation of his practice and practically working with these species will improve my knowledge. Additionally, many of these species will be unknown to myself so the exposure to these species will also be greatly beneficial.

This visit will greatly help my understanding of how and why different plants respond to their environments due to the substrate they are grown in with possible application for future green roof projects that I am interested in pursuing. It will also have practical applications for my role at York Gate Garden where we have an area that has been inspired by Peter Korn’s practice of planting into sand as a substrate. It will be intriguing to see to what extent these beds show successional display throughout the year, the level of maintenance that is required, how these beds have evolved over several years and whether we as a team can develop our own planting area at York Gate further, based on what I see and learn.

I aim to gain a deeper understanding of his practices and methodology which enable him to create low maintenance, naturalistic plantings that consider the ecology of the plants he selects. I will do this by keeping an in-depth diary and photographic record of my day-to-day activities which will include planting lists and reflections on conversations and processes.

Lower maintenance, less intensive gardening practice that boost biodiversity whilst maintaining aesthetic value is something that I am interested in and developing in my horticultural practice. Peter Korn promotes lower maintenance horticulture through his public and private designs, working with him on these projects will allow me to see this methodology put into practice. Low maintenance design is accessible to everyone allowing people with varied horticultural knowledge and different lifestyles a chance to create and enjoy beautiful, beneficial spaces. By selecting and growing healthy plants in communities that support each other and in environments where they can thrive, will also lower the intervention requirements further whilst also boosting biodiversity.

Peter also runs a nursery at Klinta that provides stock for his garden and commercial projects that he undertakes. How he and his team structure their time, manage and maintain this material and how they utilise test beds informing them of the suitability of plants for future projects will be fascinating and could influence how I plan new plantings in the future.

3. Itinerary

April 16th – Fly into Copenhagen and catch the train to Eslöv where I will be picked up by Peter before travelling to Klinta.

April 17th – 19th – Based at Klinta, working in the garden and nursery.

April 20st – Green roof project in Helsingborg

April 21st – Klinta, preparing for next project visit

April 22nd – Malmö Castle Garden

April 23rd – Trip to Gothenburg botanical garden

April 24th – Klinta in the morning preparing for Norrköping before setting off at 5.30pm.

April 25th – 27th – Norrköping project, visiting projects in Jönkoping on the way back.

April 28th – Working in the garden at Klinta

April 29th – Talldungen hotel in Brösarp

April 30th – Flight back to the UK from Copenhagen

4. Locations of projects and visits

5. Daily report of work

Day 1 – April 16th

I flew into Copenhagen and caught a train to Eslöv, where I was picked up by Peter at the station. It was a short drive to Klinta where I met Julia Andersson and their children. We had a brief conversation where I introduced myself and explained what I hoped to get out of my visit.

Peter presented me with a hazel stick that was two pronged and sharpened which turned out to be for roasting sausages over a fire for lunch. After this I was given a tour of the garden by Peter where he pointed out certain plants and explained the differences between the beds and areas. A great start and good portent for the rest of the visit!

Roasting sausages and meatballs for lunch.

The garden is quite exposed with very little wind breaks at the boundaries and surrounded by flat agricultural land. Peter does not use any chemical treatments on site, but the surrounding farmers do use Roundup extensively. Peter began to explain how he positions the plants in the beds utilising slopes and aspects, shade and exposed areas as microclimates and the difference in species selection accordingly. The majority of the plants he showed me I had never seen before.

There is a mixture of plants from Steppe and Mediterranean climates, not reflective of recreating specific environments and the plants found specifically in those areas but more of a collection of plants that will grow in the beds here. Placement of them is key. There are a lot of seed raised species that have been collected by Peter himself on his travels or by others who have sent them to him. I asked Peter about how he identifies species in the wild, does he collect samples for pressing? Photographs? He responded by saying that he spends a lot of time researching and identifying them afterwards. Google and book references are great resources for correct identification.

Peter pointed various Cistus varieties that he had received from Olivier Filippi that had not survived the previous winter. Peter has been testing the hardiness of various plants for Olivier Filippi in the Swedish climate. I Asked him about the gravel mulch applied to the beds. In his book, ‘Giving plants what they want’, he talks about the importance of a coarse surface material to break the capillary force, reducing surface evaporation. The dry surface layer can absorb any rainfall easily and be of use to the plants in the bed. Peter explained that it was more for ornamental purposes than for anything else although he finds it easier to weed the

Two areas of Julia Andersson’s side of the garden. A bank planted with Muscari, Anemone and Tulips

beds without it. Although the surface mulch is useful, there are aesthetic considerations to take into account and therefore the material used should be the same as that of the rocks in the beds, creating a much more natural feel. The particle size is also important, as in nature there are varying degrees of size from fine particles up to large rocks and this is how Peter wants it to look here too. Most of the beds are edged with Core-Ten steel, again for aesthetic purposes, which is something he plans to extend throughout the rest of the garden. Most of the beds are edged with Core-ten steel, this heats up quickly in the summer preserving heat into the evenings but in winter pulls the cold into the ground.

The site has three distinct areas. There is the nursery which consists of sand beds and mock ups of green roofs using different substrates and depths, which are used for demonstrations and as tests. Then there is the garden which has a large polythene roofed greenhouse in the centre of it. One side of this is Julias garden and the other is Peters. Both have quite different characters. At first glance Peter side seems to be more of a collection of special little plants grown primarily in sand, Julias side is soil or sand and compost mix in the beds edged with sand. Julias has much more of a woodland feel compared to Peters exposed Steppe environments. These represent different areas of responsibility and control, but both are linked by a suspended bridge over a pond behind the large greenhouse/polytunnel. The planting around the pond consists of Gunnera mannicata, Rodgersia aesculifolia, Taxodium distichum and Cercidiphyllum japonicum among others. The bed was currently mulched with straw to a depth of roughly 30cm for winter protection. You could see the Gunnera mannicata was beginning to grow as small hillocks were becoming visible where it was pushing through.

Beds of soil-based substrate with sand edging

Peter pointed out that the existing soil at Klinta is more Alkaline than Acidic (Eskilsby was quite acidic). This has meant an adjustment to what he can grow successfully here. There are much less Rhododendrons although a few do seem to be happy under the shade of a large Quercus in the centre of Peters half. There are some very old Malus trees that have a look of gnarled Olea europaea or Punica granatum, providing wonderful character. There is also a noticeable amount of Buxus that Peter mentioned he is topiarising into balls that will also add to this permanent structural layer.

The separate beds and areas contain different collections of plants and have distinct characters about them. There is a rain garden near the house where water from the roof drains to, in which are planted two Salix alba ‘Flame’. There is an Epimedium walk flanked on both sides by a two and a half meter tall Carpinus betulus hedge. A great Dixter inspired are spread over two beds, one of which is much drier than the other, where the planting becomes so tall that it completely obscures the view of a seating area in the middle during the summer and autumn.

I was given a quick tour of the greenhouse/polytunnel where I was shown some plants collected from a project that James Basson had been working on recently. These included some lovely Anemones that were described as weedy in a lawn for him. What great weeds! Peter showed me where he keeps his pots of sown seeds.

Part of the Epimedium walk at Klinta

All are sown into 9cm pots and laid out in wood lined, sand beds, covered with a mesh to protect against rodents. I asked Peter whether he still follows the sowing methodology outlined in his book and he explained that he doesn’t anymore as he ran out of seed compost one year and was forced to make a mix himself which he sowed directly into. This is a mix of pumice, sand, biochar and other additives which I will go into detail about later on. He found there was no negative impact and decided to stick to this mix. Some seeds are sown into a mix made from lava rock, sand and biochar including some species from S. America.

I was then shown the nursery area where everything is grown in sand beds, watered well once and not fed. I also had a closer look at the examples of green roofs he had on display. These are again edged in core-ten and contain different substrate depths and mixes. Pumice, biochar and sand is very light but blows off at the corners leaving dips that need filling in. Peter explained his preferred mix uses crushed recycled LECA. It has a similar weight but better appearance and does not blow off so easily. The Pumice mix is also susceptible to heaving of plants that is not seen in the other mixes.

Recycled glass in the form of foam glass blocks is used to create sculptural, crevice environments for planting. These are very lightweight and do not weather easily retaining their form for a long time.

Day 2 – April 17th

The day began by cleaning up Olivier Filippi plants in the greenhouse. Filipe’s compost mix seems quite heavy with some quite large pieces of bark in it. The pots are topped with coconut husk as a mulch/weed suppressant, the pots seemed to be quite wet or quite dry and some plants had not made it through the winter at Klinta. Whether that was because they were not hardy enough to over winter in the greenhouse or due to over/underwatering I am unsure. One such example was Salvia rosmarinus ‘Sissinghurst’. Peter mentioned he had kept it dry over the winter. We tidied up the foliage and bare rooted them using two buckets of water, one cleaner than the other for finishing off.

We continued bare rooting the Filippi plants until lunch whilst talking about Horticultural training in the U.K and Sweden. Peter was discussing how he would like to set up seminars for students with the likes of Fergus Garret and Nigel Dunnett. They would be periods of intense study combined with trips to see species in the wild in places like Kyrgyzstan. The inspiring atmosphere at Great Dixter was cited as an influence. I also asked Peter how he arrived at the methodology of gardening in sand. He said that about 25 years ago he had been experiencing a large amount of heaving of plants due to frost and the subsequent loss of plants was becoming a problem. He decided to begin experimenting with different substrates with sand being the cheapest and cleanest material available. He had been growing in pots on a sand bench and realised that any seedlings that grew in the sand could be easily removed cleanly, preserving much of the root system. His subsequent realisation that many plants performed as they do in nature, in terms of form and habit, came later using sand as a growing medium in the garden.

Cistus crispus was known by Peter to be tender in Sweden so he asked me to pot it up in a lava rock mix to keep in the green house until he could take it outside. This mix consist of Lava rock, sand and biochar with Osmocote. The other plants that we prepared were planted out in the Mediterranean area and spiral garden. Exactly whereabouts was undecided, but as I worked with him it began to seem like quite an intuitive process based on looking at the plant’s growth habit, leaf colour and texture, the hardiness information he could find with a quick google search or checking Filippi’s information on his nursery website and previous experience with similar species. Peter was quick to point out that the foliage colour does not determine his site selection in its entirety but merely gives an indication of the kind of environment it might thrive in.

Penstemon pinifolius

I watched how Peter did this and he began by getting into the middle of the root ball from the bottom and removing as much of the loose compost in a downwards motion, following this he began to tease the roots free under water. It appears that you can be rougher than I expected, tearing off old roots leaving an untangled, extremely clean root mass. Any stubborn bits of compost were removed using a sharpened chopstick which could be used to pry apart roots and get right into areas unreachable with fingers. Peter removes every bit of compost from the roots. During the cleaning process any divisions can be made, boosting the chances of success in planting.

As we planted out the Filippi plants, Peter began to talk to me about the garden and point out more interesting species in various places. We planted the Teucrium musimonum, Teucrium vincentinum and Santolina chamaecyparissus on the southside of the wall bed, where they will dry out from the wind but also get sun, amongst Lallemantia canescens. L. canescens is a little like Salvia sp. with a large blue inflorescence and grows on cliff faces in the Mediterranean where it needs a lot of wind and sun. Peters’ idea for the wall bed is an area of small shrubs dotted through a layer of small really drought tolerant rock garden plants such as Iris onocyclus and Stachys lavandulifolia, planted in drifts, reminiscent of Mediterranean scrubland from the driest areas. As we planted, I tried to get Peter to explain about how he chooses the sites for the plants, making the most of the microclimates, and about how much the conditions change over a small area in these beds. This was something I had read about in his book and felt I understood but watching him quickly assess an area and plant was quite special. Peter pointed out the curvature of the bed and explained how important the site selection was. I remembered that in his book he explained about much the conditions change over as small a distance as 20cm on an incline. I asked him to explain why he had specifically planted a Penstemon pinifolius where he had (on an east facing incline) and he explained any higher up the incline towards the ridge or even over onto the westside and it would burn. The curvature offers so much protection. The roadside (West facing) of the wall bed freezes more in winter, which is also something to consider.

Peter pointing towards where it would burn if planted higher up or onto the other side

Peter explained about when he has pots of seedlings with some ungerminated seeds remaining, he plants out the seedlings and scatters the remnants of the pot over the bed in the area he has planted. This allows the seeds to germinate in very naturalistic sites. Any seeds that find themselves in favourable positions will germinate naturally and develop into strong healthy plants, creating drifts in his plantings. Peter demonstrated this to me with several species including Astragalus angustifolius, Edraianthus glisicii, Hypericum imbricatum, Anthemis cretica sbsp. Tenuiloba, Liatris scariosa and Fumana procumbens. The substrate he uses for seed sowing allows him to remove the seedlings from the pots easily whilst preserving the root structure without damage, especially when transplanting or emptying the pots. This is a methodology that could be applied at York Gate, in the planning process of seed sowing.

If we consider where the seedlings are going to be planted out, we could tailor the seed sowing substrate in order for us to scatter the substrate over the beds with any ungerminated seeds in, to combine the natural germination and considered planting approach that Peter uses. It may not be viable in areas such as the dell, or other areas were there is a lot of foliage cover, but the Mediterranean garden, rock garden, and paved garden could be suitable sites. At all the nurseries I have worked at, seed mix is discarded after pricking out to avoid any contamination. A more sustainable approach would be to add it to the beds. The addition of biochar and feed would provide nutrients to the beds during the process. One small detail I noticed was how careful Peter is to keep any plant material out of the sun until its planted. This includes potted seedlings or bare rooted plants for the garden. Careful consideration is shown to how the sun will move and he will even use his shadow whilst planting to shield them from direct sunlight, giving them the best chance of survival.

Fumana procumbens with seed mix scattered around the planting. This was planted on the East side of the wall bed behind rocks that will provide some shelter through the winter

It took my eye a while to become accustomed to the beds and to see the all the plants amongst the gravel and rock initially, but once we began to plant the Filippi plants I began to realise how full the beds really are with emerging species. Peter would often go to plant something somewhere only to realise there was already something else there. I also began to notice the identity of the beds in more detail, the lusher Med areas with Crocus sp., Tulipa sp. and greener foliage plants to the other beds with silvery foliage and where abouts within the landscape Peter had constructed them. For example, where the beds had the longest gradual slopes and in which direction these faced, how the beds are divided by paths that also almost act like tiering and how this graduation of elevation affects temperature and shelter.

Peter manages to provide an enormous range of growing environments from exposed sites, areas of richer ground, cooler spots near water and hot exposed sites backed by walls or stones that reflect or retain heat to name a few. Providing these spots is one thing but understanding how to utilise them and how they affect each other is what makes this garden great. We finished the day by weeding through the paths, leaving some of the self-seeding annuals in place i.e., Papaver somniferum ‘Black single’ (I’m not completely sure this ident is correct, but it was a very dark, almost black, single poppy) and moving some Euphorbia sp. back into the beds.

Day 3 – April 18th

I began the day bare rooting Olivier Filipe plants with Peter in the greenhouse. Once this was completed, we began to plant them in the garden, as we did so I continued to ask Peter about the specific site selection for each species. One such plant was Dicliptera suberecta, a Uruguayan Acanthaceae family member, a perennial with simple greyish/green leaves with a felty texture with an opposite leaf arrangement and tubular orange/red flowers.

Peter placed this in a position where it would benefit from the moisture under the wall but would also get heat and sun in the afternoon. He decided against placing it in what he calls the best spot (the top two tiers the spiral garden with a south facing aspect), as it would probably burn. This intuition was derived from looking at the plant and noticing the leaf colour and texture (greener in colour rather than silver) so he decided to give it some protection from winter winds. He also noticed that it appeared to spread by runners [looking at the root system], so placed it close to the wall where some root may survive a cold winter under the stone blocks.

Dicliptera suberecta (with the white label) planted close to east facing wall

We than carried on planting Petromarula pinnata. Peter remembered he already had this in a bed and wanted to show me where it was. We compared the two specimens and the one that had been planted last year in a drier more exposed area displayed smaller leaves, reddish in colour which was probably due to stress. A decision to plant the new specimen in a damper area nearer the dry stream bed and pool was made, where it would benefit from the moister, cooler conditions.

Petromarula pinnata from last year

After coffee we continued planting the Filippi plants and then began weeding down the outside path of the wall bed and the Mediterranean beds until 5.30pm. Some of the common weeds at Klinta include the usual suspects Taraxacum officionale, Ranunculus ficaria, Poa annua and Cardamine hirsuta. All are very easily removed from the sand beds and gravel paths.

Peter planting Stachys cretica into wall bed. One plant was divided into ten and planted as a drift 40cm inwards from the wall edge on the west facing side

We broke for coffee and Julia, and I chatted about vegetable and fruit growing. They were interested in which varieties I was growing this year at York Gate and mentioned that a friend of theirs called Anette Nilsson has a small vegetable garden nearby. It is a small but beautifully arranged pottage garden which is very ornamental. Unfortunately, we didn’t get time to visit, but her Instagram @boaeng is great to look at for inspiration.

Where it was planted this year

After dinner I helped Peter and Julia prepare some plants for one of Julias clients the following day. This involved collecting the following from the sand beds in the nursery and also from trays in the greenhouse; Salvia nachtvlinder, S. lipstick, Sedum sieboldii medivarigataum, Sedum ‘Oriental dancer’, Erodium meniscari, Sedum atlantus, Achillea ‘Golden fleece’, Festuca glauca, Allium ‘Summer beauty’ and Anacyclus pyrethrum depressus.

Artemisia abrotanum ‘Coca-Cola’ aptly named for its uncanny scent

Day 4 – April 19th

Today I met Emelie and Jonatan for the first time. They both completed internships with Peter and Julia few years ago and have subsequently been employed to help in the nursery, garden and landscaping jobs undertaken by Peter. I began by helping Emelie clear a sand bed in the nursery which had previously been used to grow a grass species this had been cut and used in a planting job recently. We raked off the debris and checked for any missed plants. Emelie finished off by blowing off the surrounding debris and weeding before topping up the bed with a layer of sand for replanting with Gillenia trifoliata. Emelie pointed out to me a common weed in the nursery beds which is Tussilago farfora. It is important to recognise the root of this plant as it spreads very readily in the sand beds here, any found should be kept separate and not included in the compost.

The dandelion like flower of Tussilago forfara

All the seedlings and small plants from between the beds were lifted and taken into the garage to be sorted through and tidied up. This was an interesting process as it was great look at the differences between the seedlings of the species, noting the differences in leaf shape and colour, influenced primarily by where I had found them i.e., aspect, drainage and light. there would also be some genetic variation as a result of being seed raised. All the prepared plants were labelled and placed into plastic bags, misted with a water spray ready for the following day. Peter transports all his plants this way, re-using the bags from job to job.

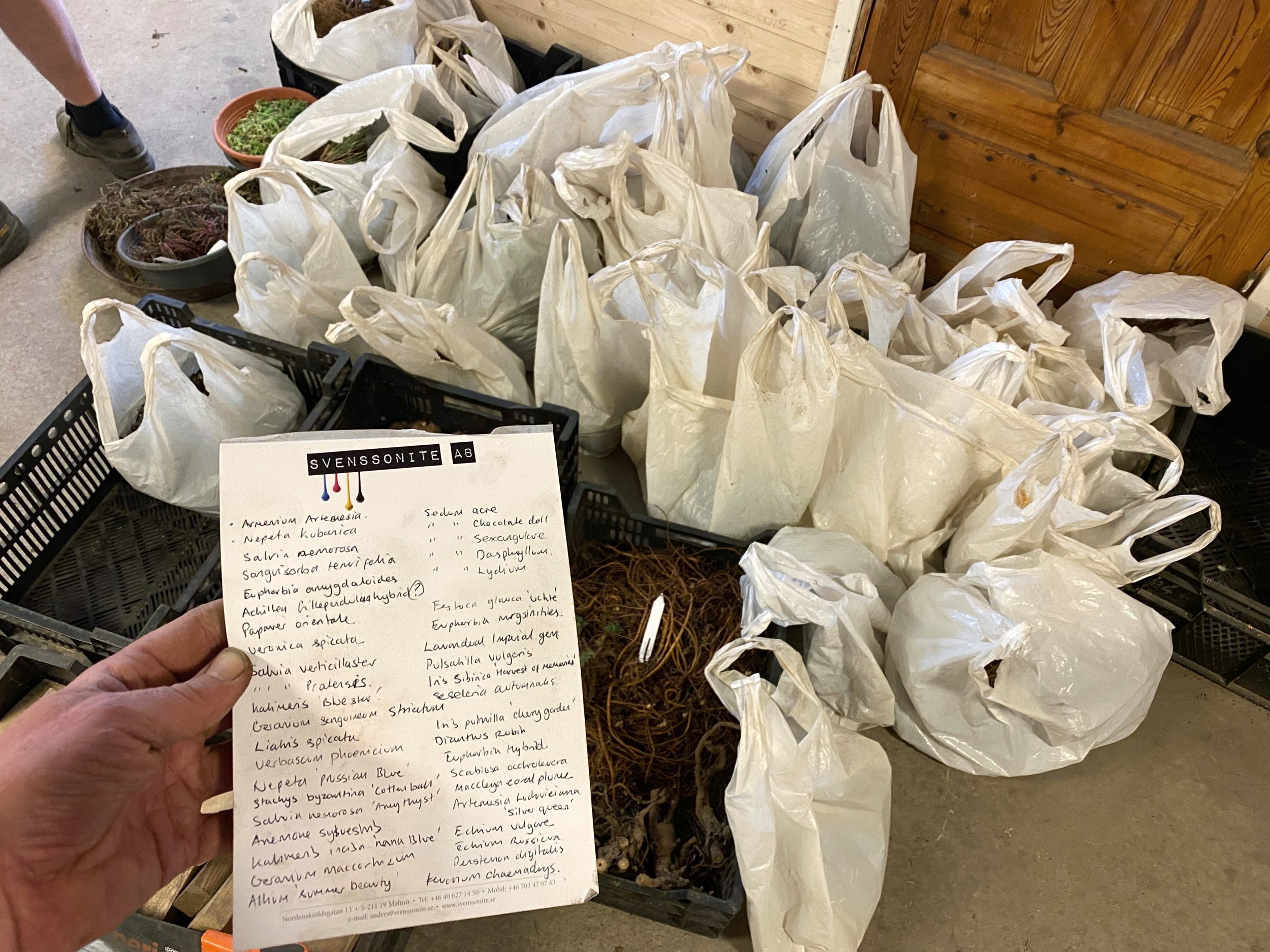

The next job was to prepare Sedums for the project tomorrow. Peter had bought in Sedum Lydium, S. ‘Chocolate doll’, S. acre and S. dasphyllum. they had arrived in 9cm pots in a peat-based compost. we prepared them by tearing off the top growth with a small amount basal tissue, he explained that they didn’t need any root material as they root extremely easily when scattered over the surface of the beds. We broke for lunch and then continued preparing plants for the following day. I collected and bagged Salvia nemorosa ‘Amethyst’, Iris sibirica ‘Harvest of memories’, Pulsatilla vulgaris, Stachys byzantina ‘Cotton balls’, Dianthus ‘Rubin’, Euphorbia myrsinities, Festuca glauca ‘Uchte’, Iris incisa ‘Nana blue’, Lavandula ‘Imperial gem’, Allium ‘Summer beauty’ and Seselaria autumnalis from trays in the greenhouse. these consisted of cuttings or small divisions that had been trayed up and grown on for this job. It was interesting to note that there appeared to be two different substrate mixes, one was a sandy, gritty mix, but the Stachys byzantine ‘Cotton balls’ was in a darker substrate that Peter explained was a pre-prepared mix for green walls. The darkness came from the biochar which was quite fine grained in this instance. I was then asked to collect an Artemisia species from Armenia from in-between the beds in the nursery. Once all the plants were prepped and bagged, I collated a plant list.

Seedlings and young plants collected from the nursery. They were lifted from the beds and also from the paths before being sorted and cleaned in the garage

Jonatan and Emelie left for the day and Peter, and I began to make a seed mix that would be applied to the beds after planting. All the seeds have been collected from Klinta over the past couple of years. Cleaning and sorting them is a big part of the winter routine here. This seed mix will create a seed bank in the substrate, adding to the display over the coming years. They will germinate at variable rates and Peter pointed out the display would likely change between years due to climatic factors with some species becoming more successful in wetter years and vice versa. Peter aims for about 40-60 species per m2. This seed mixing process was quite rough, no weighing involved but he was mindful of when the seeds had been collected, adding slightly more for older seeds. Peter also prepared a seed mix for a green wall project that would be picked up in the morning. These would be poked into the modular system holes to add interest and fill gaps, whilst he did this, I prepared some of the Artemisia sp. for the green wall project by cutting the roots to between 10-15cm so these could be fed into the modular system too.

After dinner I helped Peter water in the Filippi plants that we had planted over the

The beds in the nursery are all constructed from wood to depth of 20cm. Some are lined with Mypex, however not all are, as the whole area has a membrane under the sand. the beds are organised in rows A-E and numbered 1-42. They are in the process of trying to simplify the numbers of species and varieties in each bed to 2 or 3 instead of mixed numbers.

After helping Emilie, I began working with Peter ‘weeding’ between four of the sand beds. I was asked to collect all the Salvia verticillaster, S. pratensis, Verbascum phoenicium, Sanguisorba tenuifolia, Echium vulgare and E. russicum seedlings for a green roof project that we would be working on tomorrow. Other seedlings I found included Achillea fillipendula, Veronica spicata, Nepeta kubanica, Penstemon ‘Dark towers’ and Persicaria amplexicaulis.

Tussilago forfara root and leaf

Photo showing Salvia verticillaster, S. pratensis, Verbascum phoenicium, Sanguisorba tenuifolia and Euphorbia amygdaloides hybrid seedlings growing happily between the sand beds in the nursery

All the plants for Helsingborg bagged up and ready for tomorrow.

last few days. I had asked about the watering as we hadn’t watered anything yet and Peter explained that he liked to plant a lot and then water them all in as it was more time efficient. He also prefers to water in the evening as the plants have more time to utilise the moisture overnight. Peter waters using a high-pressure jet from a lance applied directly overhead, giving everything a good soaking. This also helps to settle the beds, removing any air pockets from around the roots. You could not do this with a soil based medium as it would puddle and create rivulets. There was very little, if any runoff, as the drainage is so good in the sand beds. Peter also spoke how he once had the moisture levels measured in the sand and it was found to hold very little water, but a lot of gaseous water vapour was present in the air pores. evidently enough for the plants to survive and grow. Peter applies a very generous amount of water when watering in, perhaps watering only once more during the year if necessary.

Eremurus cristata in the polytunnel

Day 5 – April 20th

An early start to load up the van for the green roof job in Helsingborg, totalling 300 m2 at a recycling centre. I added Baptisia ‘Lemon meringue’ from trays in the greenhouse to the plants for today whilst Peter watered the green wall modules ready for them to be picked up tomorrow morning. Peter and Emelie and I travelled to Helsingborg where we met Jonatan Malmberg. Jonatan works for a company specialising in Biochar products called Biokolprodukter who Peter has worked with from time to time. When we arrived, the substrate was already on the roof and Jonatan was digging test holes to determine whether the depth was correct across the site. this was just less than 14cm as an average.

Crushed lightweight concrete, sand and biochar

I began by marking out two circular areas for seating areas and replacing the crushed brick substrate with crushed concrete. One of the circular areas would have planted gabions around it and the other would have three foam glass block structures positioned around it, that would also be planted. Once I had completed the circular areas and defined paths to them, I began constructing and filling the gabions, whilst Emelie began cutting and positioning the foam glass blocks. Peter and I began planting up the gabions with a mixture of Geranium sanguineum, Artemisia armenia sp. and Kalimeris incisa ‘Nana blue’. Peter then began to landscape the planting areas by raking the different substrates into mounds of varying depths. The remaining gabion material was used to create a series

The green roof as we arrived on site

A completed gabion with planting and mounds of substrate in background

Peter, Emelie and I then began laying out the bare rooted plants for planting. There were three different groupings of plants for different areas. Before we began planting Peter scattered the surface with a fast-acting granular fertiliser that would be absorbed by the biochar. Peter and Emelie explained that during the planting it was important to get the roots as far into the substrate as possible and may be necessary to lay the root system on the felt layer. They also mentioned that it would be better to cover the plants with the substrate completely rather than planting them too shallowly. The felt layer would be absorbent and hold moisture against the roots. Once we had completed the planting Peter then broadcast a seed mix over the area which was lightly raked in and then watered all the beds quite thoroughly. The substrates were quite difficult to plant into and work with, as the structure didn’t break up that easily when we tried to dig into it. Peter mentioned that the substrates weren’t mixed to his usual specifications as they didn’t have as much sand in as requested. The mix ratio is usually 20% sand instead of the 10% used here. Watering the substrates also proved to be slightly problematic due to water penetration issues. It didn’t drain that freely initially, probably due to the nature of the particle size of crushed recycled material.

Having a larger proportion of sand in the mix would have loosened up the structure. Peter decided to instruct the maintenance team to set up a sprinkler system to run

Emelie laying out plants for planting

The green roof system consisted of a waterproof membrane onto of which were polystyrene boards with a felt layer on top. The substrate was spread on top of the felt membrane. The substrates for this job were made from recycled materials and there were four in total across the site. Recycled crushed concrete for pathways, crushed brick, sand and biochar for a couple of planting areas, crushed lightweight concrete, sand and biochar for a few other areas and a mixture of larger particles of lightweight concrete, crushed rock and brick and biochar for filling the gabions on site. the crushed concrete and crushed brick substrates were mixed to a ratio of 80% brick/concrete, 10% sand and 10% biochar.

Crushed brick, sand and biochar

of small hills staggered against the edge of the roof, which would also be planted into. I then helped Emelie fill and plant up the foam glass structures. this turned out to not be as straight forward as it first appeared as the substrate was quite loose when dry, so it kept spilling out. We used some smaller fragments of lightweight concrete to fill in the gaps between the blocks and backfilled the areas for planting. These structures were planted up with Festuca glauca ‘Uchte’, Salvia verticillaster in the sides and Euphorbia sp. Irises, Lavandula and Dianthus ‘Rubin’. One of the structures was planted differently using up the remaining Geranium sanguineum from the gabions. Opuntia fragilis was added to the top to prevent people from sitting on them.

After Peter had begun to landscape the substrates, with paths and seating areas

The planted foam glass blocks showing Opuntia fragilis, Lavandula and Euphorbia

overnight the following day and to also water once a week for a few months until the plants and seeds had established in this instance. I asked Peter if he had ever tried laying out the plants before applying the substrate over the top and of course he had! He told me about a job they had done where a 10cm layer of sand was applied as a base onto which the plants and bulbs were laid and then more sand was added on top after. He believed that some of the areas were too thick which meant that certain plants were not very successful, they just didn’t seem to push through. Driving back from Helsingborg though, Peter pointed out a central reservation that he was in discussion about planting up where he would use this methodology again. This would have the existing surface scraped off and then prepared with a sand bed to a depth of 10cm, the bulbs and selected plants would then be arranged on this surface with a layer of sand applied over the top afterwards. A seed mix would then be applied to the top surface. This approach would reduce maintenance time and cost for the city and reduce disruption of the road system as it would only require burning off once a year just before growth began in the spring. This could be carried out by mobile burning unit with a gas burner on an arm. The road would not have to be closed for as long, it would require less man hours for maintenance and also boost biodiversity and aesthetic quality of the planting than what was currently evident.

Halfway through laying out for planting

Day 6 – April 21st

The green wall units were being picked up today, so we began by moving them from the hardstanding area outside the garages to nearer the front gates. 16 green wall panels in total. As we did so, we spoke about the planting for the green roof job in Helsingborg, Peter explained it would take about 3 years for the plantings to mature and begin to look established, as it was quite a low budget job, so the plants used were quite small. After moving the green roof units, I began to help Jonatan in the nursery constructing three new raised beds for an area. We began by clearing the areas they were to go in, by weeding through and collecting usable plants. The surface was then raked level. Jonatan left at lunch, and I carried on constructing a few raised beds for Julias kitchen garden with Peter, these would be used to grow Raspberries in. A few Danish trolleys of plants from Reinbeck had arrived yesterday whilst we were in Helsingborg, so after lunch I unloaded these and sorted them out for the jobs that they would be used on. The majority were for a garden of a hotel owner that we would hopefully be visiting next Friday. These plants were moved to a shady area at the front of the greenhouse where they would stay until needed. Peter showed me the local sandstone that he had found whilst digging a pool area in the greenhouse, it was quite varied in colour with some bits being much redder than others and some very yellow.

Lomatium colombianum and Iris bucharica in the background

Corydalis ‘Canary feathers’

Peter had previously mentioned that the existing soil on the site at Klinta varied between his and Julias sides, Julias being much richer in clay which led them to believe it used be a seabed at some point in the past. Klinta, he told me, meant cliff in Swedish. He had been collecting this sandstone to use when he constructs a cacti garden and explained that he will cover the area with a glass roof about 3-4 metres high and will have brick walls at the back on the north and west sides, meaning it will get extremely hot in the summer. He will be able to grow various Agave sp. that are not hardy in the Swedish climate, such as Agave montana. we spent the rest of the afternoon collecting and preparing plants for a job in Malmö the following day. This was a public park that contained several show gardens, one of which was Peters’ that he had completed 8 years ago. I was very keen to see how his plantings had matured here. I spent some time cleaning up and dividing some lavenders which were to be used in areas to stop foot traffic over the beds which Peter explained had been a problem. After dinner I walked around the garden and took some photos, many off the tulips are now beginning to open and leaves are emerging on the surrounding trees. The garden has really felt like it has started to move whilst I’ve been here, the difference from day to day is quite noticeable.

Iris cycloglossa x aucheri clone #3

Paeonia ‘Dancing butterfly’ in the nursery sand beds at first light

Day 7 – April 22nd

Todays’ job was at Malmö Castle Garden, where there are several show gardens by various designers and a large kitchen/allotment space. Peters garden was completed eight years ago and today we would be completing some maintenance and replanting with the gardeners on site and a couple of students who were on placement. First though, Peter and I visited a potential job for a private client in the suburbs of Malmö. It was quite a traditional garden space with a large lawn to the rear and a number of square core-ten edged beds to the front currently filled with Geraniums, Hydrangeas, Salvias, Hellebores, Nepeta, Roses and small trees like Magnolias. The garden was currently being maintained by a local gardener who had contacted Peter to advise on replanting. A lot of the plantings were currently in the wrong positions to really thrive, and the current selection was a little underwhelming, Peter offered advice and suggestions for planting and agreed to help further if he could have creative control over the planting of the two square beds that flanked the entrance stairs to the property. The client and gardener seemed very happy with his suggestion of creating a firework like display here using a lot of tall grasses and spiky plants such as Cortaderia selloana, Pennisetum macrourum, Stipa gigantea, Jarava ichu, and then a lot of Knifophias, Lobelia tupa, Eupatorium capillifolium, dark red and orange Chrysanthemums, Salvias, Veronicastrums, Echinacea ‘Tomato soup’.

Peters garden at Malmö

We arrived at Slottsträdgården at about 10 am where we met Emilie, Lina and two students who had begun work on Peters’ Garden, weeding through the beds. I began by pruning two Santolina Chamaecyparissus shrubs, removing some of the dead and allowing light into the centre. Peter started pruning some of the larger shrubs and trees in the garden and then we began planting once we had cleared up the debris. Peter gave me the responsibility of planting the Lavandula (that I had cleaned up yesterday), Ballota psuedodictamnus and Helianthemum ‘Georgeham’. I was instructed to plant naturalistically in areas that evidently received a high volume of foot traffic, as a way of preventing access onto the beds. A lot of the planting in these areas had been trampled and damaged, as a result of people climbing on to the tiers and jumping off. The Ballota pseudodictamnus was interplanted with Salvia greggii ‘Blue note’ and The H. ‘Georgeham’ was put in areas where it would spill over the edges of the stone blocks. I also planted Euphorbia sp. through a few the beds.

A hand trowel for scale, showing the depth of the sand beds

Once all the maintenance and planting had been completed the beds were scattered with fast acting fertiliser in pellet form and then watered quite heavily. Peter then sowed an annual seed mix over the beds that would self-seed throughout the garden over the next few years. We then applied a fresh layer of sand over the beds to a rough depth of 3-5 cm and then planted Chrysanthemum indicum hybrid ‘Oury’, ‘Ceddie mason’ and ‘Red velvet’ throughout. The garden will be closed off to the public until June to allow the plantings to establish and settle. We had a final clear up and then drove back to Klinta for dinner, stopping to see an installed green wall on a car park that had been completed 4 years ago in Malmö city centre.

The modular green wall systems that Peter has been involved planting have had their problems as he explained. Initially irrigation pipes ran every 3rd row but due to a low-pressure system the water penetration through the rows wasn’t great and you could see where the water was reaching to, reflected by the lushness of the planting.

After this, we visited one of Julias current design jobs which was in another area of Malmö. The property had recently been bought and the owners wanted the landscaping and garden redesigning. having spoken to Julia on previous evening about this project I knew she planned to suggest a carpet of Pachysandra terminals on the approach to the house, with the simplicity of the planting aiming to enhance and show off the architecture of the property. The back garden space was quite interesting with a large Malus that dominated the space centrally, but it was not in particularly good shape. Julia was trying to persuade the clients to keep it but to address the issue of its shape by hard pruning it, at the advice of an arborist. The rest of the planting in this area would be herbaceous, but of a strong design to reflect the angular nature of the architecture. This was a very interesting insight into the two different approaches that Peter, and Julia have towards planting design, and how they complement each other at Klinta.

Emelie and Lina discussing the planting

All the beds in this garden are constructed from pure river sand to 10cm below the level of the paths. The tallest beds were roughly 1.5m in height and these were the ones that had the Santolina chamaecyparissus planted in them. The sand was still holding a considerable amount of moisture below the surface, the top 2-5cm was dry but below this the sand was cool and moist. The beds were covered in a gravel mulch of quite a large particle size giving a very natural landscape look. Peter had mentioned previously that this garden had received mixed responses due to the look and style of planting. It is not necessarily what many people associate with a garden being very dry and naturalistic and it had also suffered considerably with theft of plants once it had initially been planted meaning that Peter had to reconsider his plant choices and begin to use less rare and desirable plantings in this instance. The plot itself was also not symmetrical, but the way that Peter had constructed the beds made it appear so. The back of the plot was approximately 1 metre wider than the front meaning that when Peter constructed the garden the appearance of order and formality in the hard landscaping was difficult. If it had not been pointed out though I am not sure I would have noticed!

The completed planting and sand mulch before watering

These irrigation pipes were also not sitting correctly in the walls which meant they were not operating efficiently. As a result of these issues the irrigation pipes now run on every row and are used once a week. Running for 6 minutes on the top rows and 4 on the lower half. The additional time for the elevated rows is to allow for the water to travel up to the top of the green wall system, meaning each row gets an equal amount of water. Any replanting has to take place in situ as these units cannot be easily removed once installed. Peter explained that the plant choice in replanting is limited as it is necessary for the plants to have a short root system so that they can be inserted into the units on site. When planting these units up at Klinta plants with a longer root system are trimmed down to around 15cm and inserted into the modular system as it is filled up with the substrate.

An installed greenwall in Malmö

Day 8 – April 23rd

Today I caught the train from Lund to Gothenburg to visit the botanical gardens and to meet Thomas Pouzetti. Thomas was a previous student of Peters’ whilst he was at Eskilsby. He is now responsible for several areas at the botanical garden including part of the Rhododendron valley. When I arrived, I was met by Thomas who gave me a brief tour of the greenhouses and then he left to complete a few jobs and have lunch. I was allowed to wander freely around the nursery and greenhouses that currently are closed to the public due to reconstruction work that will be completed in 2026. This felt like a real privilege, and it was incredible to see so many plants that I had only seen before on the internet or in books. Gothenburg botanical garden holds the largest collection of Dionysia sp. some of which were in flower during my visit, but the orchid houses simply took my breath away! They were full of the most incredible inflorescences, colours and scents with over 1500 varieties and species. I took so many photos that my camera battery was running low before I had even been into the wider garden areas.

Helicodiceros muscivorus

Thomas found me after his lunch, still wandering slack jawed around the glasshouses and then proceeded to give me a tour of the remaining glasshouses and outside areas. Gothenburg botanical garden was established in 1921 and the Dioscorea elephantipes I was shown in the succulent house was gifted to them in 1922 by Kew, making it 100 years old! We walked up through the Pinetum and Rhododendron valley, which are divided into European, Asian and American areas that provide a succession of blooms throughout the year. We continued up through the Rhododendron valley to the rock gardens, that again were divided into distinct climatic regions. All these areas were very carefully curated and planted using only species from the geographical areas they represented. At this point Thomas had to return to work and I continued to explore the gardens before walking back through Gothenburg to catch my train back to Lund.

Paphiopedilum appeltonianum

Day 9 -April 24th

Peter and I began the day by bare rooting and planting the remaining Philipe plants and then we gathered everything we needed for a civic planting job in Norrköping that we would be working on for the next few days. This included lifting plants from the nursery bed and making seed mixes for five different areas. We set off for the drive to Norrköping by 5pm, arriving at 10.30pm. on the way up Peter explained a bit more about the job ahead. His first visit was in the Autumn to agree to take on the project, he then re-visited at the beginning of April to meet with the architect, Peter Lynch, who would be overseeing the job. Peters brief was to develop an insect friendly planting coupled with his landscaping that would promote biodiversity in the area. A camera had been developed and installed at the site to record the insect population 24hrs a day. There was to be five distinct planting areas: a steep south facing slope, an area of fine sand, an area of coarse sand, a Swedish meadow area and woodland edge.

Peter Lynch had commissioned a dancer called Anna Asplind to dance at the site with the intention of this informing Peters planting in terms of rhythm and as part of the research process. The overarching aim of this project was to provide a space in Norrköping that had been designed and planted to promote interaction between humans, insect and animal life using this shared space. Peters planting had to promote biodiversity through extending the flowering season and nectar sources throughout the year and by providing as many habitats as possible.

There are lots of areas like this in cities in throughout Sweden and in the UK. Areas that are not parks but are also not quite entirely wild spaces. These non-spaces provide a multitude of uses for a wide variety of people and animal life. In this instance the site would continue to be maintained by the local council or municipality. The hope of Peter Lynch was that this could be a really great example of what can be done with these areas on a wider scale, for a relatively low budget and with low maintenance requirements.

Day 10 – April 25th

We arrived at the site in Norrköping at 7am and met Anna Asplind and members of the local municipality gardening team. We began work on the site by raking the south slope as Peter wanted to remove as much moss, debris and dead grass as possible before spreading fine sand over the area which would help to repress the grass growth and create a very dry, hot site for sowing. This south facing slope was dotted with several trees and shrubs including Sorbus, Betula, Pinus and Rosa species. Some of these would be crown lifted to allow a greater amount of light to reach the slope and some would be removed entirely over the next couple of days. The next area to rake was the plateau at the top of the slope and over onto the north facing bank.

The steep south facing slope with moss and debris raked to the bottom

Whilst Anna, the maintenance team and I raked these other areas, Peter began spreading the fine sand over the site. All the sand was transported onto the site in the bucket of a small tractor and then raked into shape by Peter. Watching Peter contour these piles of sand was great as you could see quite clearly how carefully considered this process was. All the created mounds followed the natural contours of the site making them appear very natural. These mounds were then walked on to create a compact base layer that will be good for burrowing insects, before being re-contoured again using a coarser sand on top. In the most exposed areas no coarse sand was added. The areas with only a layer of fine sand would be the harshest areas, reminiscent of Steppe environments.

Although some of the trees on the south facing slope would be removed the intention would be to replant these areas with smaller fruit trees and shrubs that would cast less shade and provide more for wildlife. The woodland area would have a few Quercus sp. planted in the next year, in order to succeed the mature Fraxinus excelsior trees that will probably only last the next ten years or so.

Planting with the volunteers from Naturskyddsföreningen

Peter and I had dinner and then I was treated to a slideshow of his trip to Kyrgyzstan and some of his other projects including a hospital in Jönköping, a series of rain gardens in a parking area, a sandbar in Vellinge where 27 different seed mixes were used over a 1400m2 site, and some photos of Klinta throughout the seasons and at different points of development. This was great to see some images of these sites and Klinta at their peaks, it never ceases to amaze me how much growth can occur in a season and how different Klinta looked in July and August. The images of Klinta allowed me an insight into the successional layering and concentration of plants per metre that Peter advocates.

This process of raking to remove the moss that was growing amongst the grass was very labour intensive but essential to the job as Peter explained that with milder winters due to climate change, the moss would take over the sandy areas depriving habitats and reducing biodiversity. This process could have managed and achieved through controlled burning and was discussed at an earlier stage, however due to the location being in the city it was felt that it would not be appropriate in this instance.

The plateau at the top of the steep slope partially landscaped with a covering of fine and coarse sand in places

Later in the afternoon we began to create pathways along the south slope. These pathways were almost just marks on the landscape, very reminiscent of the paths created by grazing animals that you see in the Yorkshire dales and elsewhere. I asked Peter about this, and it was confirmed that this was the intention. The south slope was influenced by a recent trip to Kyrgyzstan and would be a very exposed, almost Steppe like environment. In the evening we were expecting a number of volunteers from a local branch of Naturskyddsföreningen to assist us finishing off the paths, raking and to begin the planting. Naturskyddsföreningen are the Swedish society for nature preservation and are Sweden’s largest environmental organisation. They are made up of volunteers who are involved in projects at local and national level across Sweden and internationally. We broke for Fika at 6.45pm before clearing up and finishing for the day.

The creation of the paths that traversed the slope

Day 11 – April 26th

We arrived at the Norrköping site for 7am and work commenced on removing some of the trees along the south slope. The felled material was chopped up to create an insect habitat next to a hollow Ash stump. Just after 9am some large boulders were delivered that would be incorporated into the landscaping to provide seating areas at certain points. Peter moved these into their final positions using two iron bars, Peter explained this was how he moved the boulders at Eskilsby when he was creating the landscape there. We were at that point informed that there would be no more sand delivered that day as there was a shortage of municipality trucks in the region, the remaining 70 tonnes of sand would be delivered at two-hour intervals the following day. This delay would potentially push the job into a fourth day.

Felling the trees on the slope

We continued to position the boulders and used the remaining sand to create some new mounds in other areas. All the material that was dug out in the process of placing the boulders in their final positions was used as the base material for these new mounds, nothing was wasted. I raked over the area on the cliff top/plateau area and as this was finished in terms of landscaping, we began to plant it up and sowed the seed mix for the fine sand areas and half of the south slope.

I got speaking to Lars, who was the foreman working for the municipality and he proceeded to tell me about the bedding displays that Norrköping are famous for. These displays are put together using Cacti, Euphorbias and succulents and form elaborate displays on roundabouts and park spaces throughout the city. Lars invited Peter and I to have a look at the greenhouses where they keep the larger plants overwinter. This turned out to be a short walk from where we were working so we spent an hour being giving a tour by Lars. I was impressed by the cleanliness and how organised these greenhouses were. Some of the specimens have clearly been very well looked after for quite a few years. It was evident from Lars that these displays are a source of pride for the municipality, and they clearly enjoy creating them.

We continued to position the boulders and used the remaining sand to create some new mounds in other areas. All the material that was dug out in the process of placing the boulders in their final positions was used as the base material for these new mounds, nothing was wasted. I raked over the area on the cliff top/plateau area and as this was finished in terms of landscaping, we began to plant it up and sowed the seed mix for the fine sand areas and half of the south slope.

Positioning the boulders for a seating area

The boulders for the seating area overlooking the south facing slope, in their final positions. The sand has been applied to the area and just needs a final rake over to landscape before planting and seeding

Day 12 – April 27th

We arrived at site for 7am again and awaited the first of the deliveries of sand for the day. When it arrived at around 8am we inspected it and found it to be a different quality than the deliveries before. It had a higher clay content than previously, evidenced as it could be compacted into a loose ball. This would be good for insects as they would be able to burrow into it more easily.

We continued to use the sand as it arrived to landscape the remaining areas and then commenced the planting and sowing. The deeper areas of sand were planted with Prairie plants such as Ratibida sp, Symphyotrichum sp, Verbascum sp, Chrysanthemum sp, Verbena bonariensis, Liatris sp., Echinacea pallida, Persicaria amplexicaulis, Linaria dalmatica among others.

Peter Korn, Peter Lynch and Anna Asplind discussing the landscaping of the mounded circular area on the plateau

On the plateau was an area that Peter the architect had spent time working on. This consisted of a circular area of mounded sand surrounding some exposed rocks that he been chiselling to allow a person to lie down amongst them comfortably. The mounds consisted of coarser sand to the outside and fine sand on the inside slopes. The coarser areas looked drier and more exposed and would be planted with rock garden plants, however the main planting would consist of Stipa pulcherrima. In the fine sand areas, it would be Stipa calamagrostis. This mixing of sand (the fine and the coarse) is a way of being able to use more species. From a design perspective it would appear strange to have the range of plants used in the same type of sand. We completed the remaining landscaping, planting and seed sowing, cleared up and packed the car for 5pm, ready for the drive back to Klinta. Peter has subsequently returned to Norrköping to check on the progress of the planting, adding Potentilla anserina, which will form a silvery carpet in the conditions present, Cortula potentillina and Bellis perennis to the circular mound on the plateau. There have also been some issues with people walking on the sand mounds, but Peter mentioned the germination has actually been better in the footprints due to the compaction which has held the moisture a little better.

Peters’ instructions for watering which were given to the landscaping team of the municipality, who would be responsible for the maintenance of the site, were for 4 cubic meters of water to be applied to the areas of coarse sand the next day. The fine sand areas and slope were not to be watered. I asked Peter what the estimated number of plants we used on this job was and we worked it out be between 3/4000. A small amount for Peter!

On the drive back to Klinta Peter wanted to stop at the Hospital I had seen in his slideshow the previous night. This green roof project had been completed 8 years ago with a 60cm thick concrete roof above a cancer treatment ward. This meant

The car park rain gardens

We continued our journey back to Klinta and I began to think about what I had just seen and the project in Norrköping. I asked Peter how he felt about returning to projects that are perhaps not being maintained to the standard that would be preferable. His response was that if the people are trying to maintain them as well as they can with the resources at their disposal, he continues to maintain a dialogue and work with them to develop the areas. He mentioned the application of the gravel mulch as an example. He pointed out to the team that this would prevent the annual self seeders from adding to the display, but the prevention of weeds was

that the substrate weight wasn’t really a consideration as the weight bearing capabilities of the roof would be very high. The green roof was landscaped, planted and is maintained by the hospital gardening team with Peter providing the plants and acting in an advisory role due to budget limitations. Peter spoke about how the build and landscaping wasn’t perfect, so it was a good example to show me. One of the beds is lower than the path which has meant it got very wet and has had additional drainage added since completion. The sand used was too fine and so it was also very difficult to create mounded areas for planting, meaning the landscaping is quite flat and less dynamic with a reduced range of microclimates for planting. A lot of the planting is in clumps rather than drifts and was noticeably concentrated in easy access of the paths that ran through the roof area. Originally there was only a gravel mulch (5-10mm) applied to a raised area to the right of the entrance to the roof, the hospital maintenance team had subsequently added a finer gravel as a mulch to the lower areas which were originally left as sand, to reduce weed growth and maintenance requirements. This was added far too heavily and was quite thick in places (10-15cm). this would certainly prevent weeds but would also prevent any self-seeding plants from spreading through the planting. Peter had advised in regard to these issues, and continues to work with them on the plantings, but ultimately, they are responsible for what they do here. We then visited the rain garden that I had also been shown. The substrate here was sand and biochar under a gravel mulch in the areas for planting. In between these pockets it was pure gravel on top of a felt-like membrane. To the front of the hospital were a long stretch of concrete troughs that Peter had planted up 4 years ago. He had replaced the existing shrub planting, removing 20-30cm of the soil and replacing with sand. Into the sand he had planted a range of perennials that were clearly happy, some were beginning to spread and could be lifted and divided if necessary. This was a pilot area that would eventually replace all the existing shrub planting in these troughs across the hospital site.

Landscaping at the hospital project in Jönkoping

seen as a greater priority. As for the sunken bed on the roof, a solution that he presented to them was to lift the plants and raise the level of the substrate but unfortunately there was no budget for this. These become opportunities to learn from, to see what plants work in these areas and allowing experimentation and a greater range of plants that can be suggested and used. Peter says he is still learning from his plantings even after all this time and the experience he has, which I found very refreshing and reassuring. We arrived back at Klinta around 11.30pm.

Day 13 – April 28th

Today was spent working in the nursery and weeding in the garden with a Swedish student named Ylva. Ylva had arrived at Klinta for a four-week study programme on Monday and had spent time working with Jonatan and Emilie, whilst Peter and I had been in Norrköping. We spent the day removing Salvia staminea from the pathways where it would become too big and prevent access later in the season. We then had a walk around the garden appreciating how much it had begun to change whilst we had been away. The garden seems much greener than when I first arrived. We then prepared the plants for the hotel job in Brösarp the next day, using Bellis perennis we had lifted from the paths in the garden and Stipa pulcherrima we had lifted from the beds.

After dinner Peter showed me his seed sowing method which had changed from that which he wrote about in his book. His previous method used a seed sowing compost with a fine layer of sand on top onto which he sowed the seeds before topping with grit. The sand provided an even, clean surface of even moisture that would allow for an even germination of viable seeds. Peter now uses a seed

Peters seed sowing mix consisting of 80% pumice, 10% sand, 10% biochar

sowing mix of his own devising consisting of 80% pumice, 10% sand, 10% biochar. Osmocote, basalt powder and clay granules are added at a rate of 2.5 decilitres per 200 litres. This mix came about as he ran out of seed sowing compost one year, subsequently realising that this mix gave him better results. Previously Peter had to wash all the soil-based substrate from the roots of the plants grown before planting and explained he lost a high proportion of his plant material this way. Fabaceae members in particular really disliked any root disturbance, using the pumice-based mix he finds that there is little root disturbance, and the pumice mix allows him to plant out seedlings directly. He joked that he now has the opposite problem with Fabaceae – Too many! When sowing seeds Peter uses 9cm pots, he doesn’t tamp or compress the surface onto which he sows the seeds, sowing thinly and then topping with grit. For very fine seeds he sows them directly onto the grit and lets them fall between the particles. These are then watered using a lance and hose with care taken on the first pass not to flood the pots and wash away the seeds. He does not use a propagation unit as he prefers natural germination, placing the pots onto sand in the polytunnel. These are watered 2-3 times a month through the winter and every 2-3 days during the spring and summer.

The germination area inside the polytunnel

Day 14 – April 29th

I spent the last full day in Sweden working with Peter, Jonatan and Ylva at Talldungen, the hotel in Brösarp. This is a project where Peter has complete creative control and autonomy over the plant choices and the complete trust of the clients. There are two houses for the owners with contrasting styles of planting. One was requested to feel very lush and foliage heavy and the other soft with fruit and blossom trees. The hotel itself feels very Mediterranean and yet there are none of the plants that you would automatically associate with this feeling such as Lavandula, Oleas etc. The planting consists of a very complex and colourful display against the hotel, inspired by Great Dixter which the hotel owners visit frequently. The planting then blends out into the wider landscape becoming much more meadow like. A large, mounded area was created to hide a road that passed in front of the site and to also aid this seamless blending into the landscape.

The hotel Talldungen

This photo aims to show how much moisture remains held in the sand. There had been no rainfall for three weeks in the area and you can clearly see how moist the sand remains 5-10cm below the surface, which had dried out, breaking the capillary force and reducing surface evaporation.

The car park area was seeded with an annual mix that would gently spread into the areas of less traffic and I planted the Bellis that we had collected amongst the boulders tat provided barriers. These would also seed about given time. On the drive back to Klinta, Peter told me about a meeting he had yesterday about landscaping a few schools in Stockholm. This sounded like an exiting project that would hopefully be a pilot for how schools can be planted and landscaped in the future. Peter spoke about his desire to work with the teachers at each of the schools directly to tailor the projects specifically to the needs and interests of each individual school. He is very keen to not create a one size fits all approach that has been the case previously in these settings. In the evening I had dinner with Peter and Julia, said my goodbyes and expressed my gratitude for the hospitality and opportunity I had been given and then prepared for my journey home the following day.

One of the beds close to the building that is inspired by Great Dixter

6. Summary and findings

This research trip came to fruition as a way to learn about how to improve a planting area at York Gate and a desire to learn more about Peter Korn’s methods for producing low maintenance, species rich, naturalistic designs that also boost biodiversity through careful species selection, creation of habitats, substrate choice and landscaping. To this end it has been a success and I have a greater understanding of how Peter works and the thought process of that underpins these projects and plantings. I was fortunate to be able to spend two weeks with Peter and Julia and within that time managed to experience a broad swathe of the type of projects that they are involved in, from the green roof project in Malmö through to the planting at Talldungen hotel. All the projects were different and had varying requirements, but the end result was the same; low maintenance, beautiful, naturalistic designs informed by plant trips to see how, where and what species grow in communities in their natural environments and the careful research and understanding of how wildlife will interact and utilise the landscaping, to promote biodiversity.

About ten years ago, whilst at Eskilsby, Peter began to take on work from private clients, primarily with a focus on minimal maintenance plantings. His focus now is on creating plantings that have year-round interest, high diversity, low maintenance requirements and the use of recycled materials. I asked Peter how his work had evolved, and he explained that the creation of landscapes early on was always with the ecology of plants in mind, but because these grew so well in the conditions he provided, the insects and animals came. At Eskilsby he began to notice new insect species and also an increase in the number of people visiting to photograph this insect life, ‘mostly old men’ was how Peter described them, but it led him to the realisation that these environments were not only beneficial to the plants he wanted to grow but also in boosting biodiversity. Over the subsequent years he has developed a greater understanding of which type of environments and the habitats they provide, and which type of plants support different insects and wildlife. He now ensures his designs are good for insects but also incredibly beautiful for people.

Before I arrived in Sweden, one of the questions I was asked by people regarding the method of growing directly into sand was how do the plants meet their nutrient requirements in order for healthy growth? I supposed that they accessed some nutrients from the sand as it is not an inert substance, but surely, they needed more than that which would be available to them. Having seen Peter and Julia’s Garden at Klinta and how well everything has established, and through conversations with them both, I now feel able to give much more informed answer to that question. Firstly, Peter doesn’t always grow in pure sand on its own. The substrate for many projects often contains Biochar and a recycled material as a constituent part of the mix. The Biochar acts as a nutrient sponge absorbing leaching nutrients and trace elements and making them available to plants as and when they need them. Where sand is the primary substrate, it is often used on top of the existing subsoil/topsoil, which the plant roots will eventually penetrate. Many of the planting projects Peter completes are top dressed with a fast-acting granular fertiliser to also boost growth as well, this is added to help the plants establish and to get their roots growing. The sandy substrate is a good medium for root growth which Peter believes to be fundamental for healthy plants, which I am sure everyone will also agree with. A plant with healthy root system will be able to access moisture and nutrients from a greater area and depth, leading to subsequent healthy growth. It is important I think to reference something Peter touches on his book at this point relating to what people often associate with ‘healthy growth’ – large above ground growth with lush foliage and a profusion of floral interest. This is a possibly because of a tradition of growing into nutrient rich fertile soils that have been cultivated, with the plants often being given additional feeds throughout the year, similar to how vegetables are grown, where the desire is for large leaves, especially with salad crops. These highly fertile growing conditions put less emphasis on the plants developing a large, deep root system. This is not how things work in nature and is reflected in the plantings Peter creates. Growing in these sand-based substrates means there is little available nutrients for growth forcing the plants to develop a large root system. The reduced nutrient levels also have a morphological impact on the plants grown, leading them to develop smaller foliage size with a hardened cuticle which makes them more resistant to any sap sucking pest such as aphids. Although the foliage mass is reduced, the inflorescence size remains the same as does the flowering height in most instances. The large root system also helps to anchor the plants better meaning they are often more stable in the ground.

The use of Biochar is something that I would like to explore further, and is I believe something that we as gardeners can utilise for many benefits. Biochar is created by the process of pyrolysis and is conducted in the absence of oxygen. Organic material is heated to between 200-700C to remove most of the Oxygen and Hydrogen containing molecules. The resultant material is a Carbon structure whose surface is covered in Oxygen containing groups that facilitate ion and electron exchange, leading to its ability to absorb and release nutrients effectively. Biochar differs from charcoal in the sense that charcoal is often much larger in size and is sometimes soaked in additional liquid fuel, it can also often contain large amounts of residual organic matter which can be phytotoxic. To be considered Biochar the product must contain 0.7 as the maximum H/Corg ratio according to the IBI and EBC. Research into Biochar suggests that it has a potential usage in carbon sequestration and as an additive to correct/alter soil pH (it has a liming effect).